As Instagram and love Island groan under the weight of super-plumped lips and uber-smoothed brows, unregulated and barely trained practitioners dominate a £2.75 billion (and growing) filler industry – often with dangerous results

Jessica Myott is only 24, but she has been having dermal filler injected into her lips every three months since the age of 18. ‘That sounds like a lot, but it doesn’t last on me,’ she says. Her small lips have always been her biggest insecurity, she adds, ‘So I feel like I need to have it done.’ As do her three sisters. Then there was Megan Barton Hanson, a contestant on last year’s Love Island, pictures of whose pneumatically filled face flooded social media, encouraging most of the young women Myott knows to get the look too.

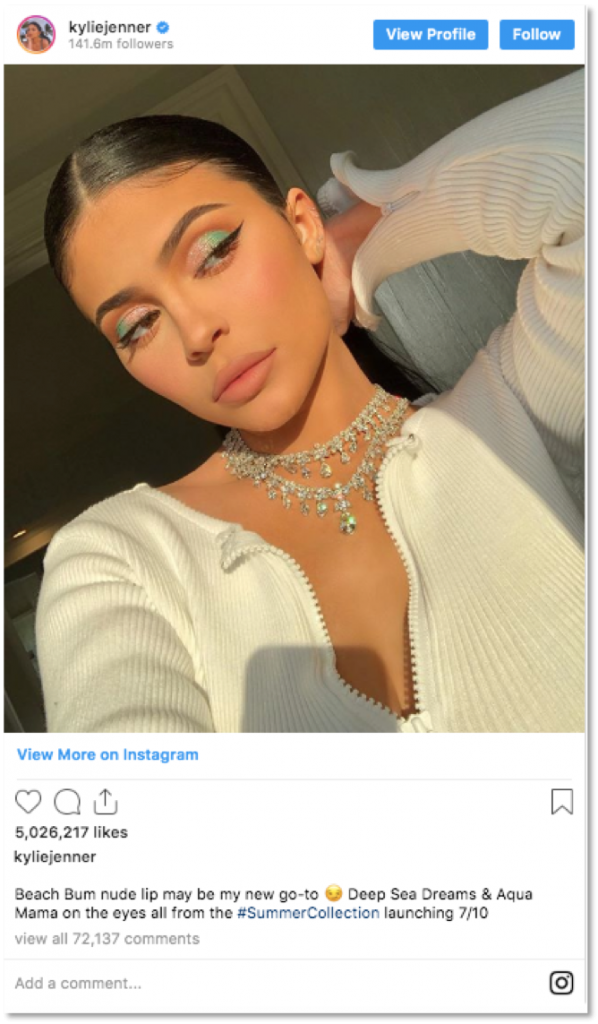

The ‘injectables’ industry is already worth £2.75 billion in the UK and seems only set to swell. If you were to trace the origins of the craze, you might start with 21-year-old Kylie Jenner, the youngest of the Kardashian/Jenner clan, who built a cosmetics empire on the back of the pout she first had filled at 15 – propelling her to become the world’s youngest self-made billionaire earlier this year.

Homegrown reality TV stars have normalised the look further. You don’t need to have seen an episode of Love Island, which will finally hang up its thong bikini on Monday, to be familiar with contestants’ cartoonishly pretty aesthetic: lips plumped like bolster cushions; unnaturally prominent cheekbones pulling jawlines taut as drums.

Their real appeal is that they weren’t born this way: pictures of this year’s headline-grabber, Maura Higgins, in her thin-lipped schooldays, have been doing ecstatic rounds on Instagram with the caption: ‘Proof fillers change lives.’

‘Casting directors cast girls that look a certain way, which fuels an interest in the media to break down exactly what procedures they’ve had done. That in turn feeds these before-and-after pictures,’ says Ashton Collins, director of Save Face, a government-approved register of accredited cosmetic practitioners.

Clinics caption these images and their own handiwork, ‘using hashtags like #loveislandlips and #loveislandlook, which girls search for during the ad break. They see something on offer for £99 and off they go.’

A-list facialist Vaishaly Patel has observed the trend in action at her Marylebone clinic: older clients use fillers to restore the lost contours of youth; younger ones to transform their facial topography altogether. ‘They’ve all got this look –the drawn-in eyebrows, the lashes, the lips, the cheeks. Instagram’s a huge influence,’ she says.

‘The main [filler] I always see is right in the apples of their cheeks because even when they’re lying down on my bed the cheeks still stick up. Or sometimes you see the lips first before the person.’

It would be easy to sneer, but Dr Nick Lowe, who pioneered cosmetic Botox injections back in the early ’90s, has lamented his part in letting the genie out of the syringe. ‘Body dysmorphic syndromes and a terrible loss of self-confidence’ are rife in young girls, he said this year. ‘They’re convinced that looking like a celebrity is going to make them happier and more successful.’

It would be easy to sneer, but Dr Nick Lowe, who pioneered cosmetic Botox injections back in the early ’90s, has lamented his part in letting the genie out of the syringe. ‘Body dysmorphic syndromes and a terrible loss of self-confidence’ are rife in young girls, he said this year. ‘They’re convinced that looking like a celebrity is going to make them happier and more successful.’

‘There’s a pressure to have stuff done because they feel like everyone is having it,’ agrees Dr Jane Leonard, a GP and cosmetic doctor who does aesthetic work in London, Liverpool and Manchester. ‘If they’ve screenshot millions of things off Instagram, that’s a red flag – all these different faces of girls that don’t even look like them.’

Her prices (roughly £280 for 1ml of filler injected) tend to preclude those looking for a lot of bang for their buck, but around two out of every five of her clients bring in filtered photos of themselves and ask her to turn them into reality, a phenomenon that has been dubbed ‘Snapchat dysmorphia’.

There’s an argument that if a non-surgical procedure boosts someone’s confidence, what harm can it do? The permanent silicone fillers that disfigured actor Leslie Ash when she became the unwilling poster girl for the ‘trout pout’ in the early noughties have largely died out. The modern breed, which often go by brand names such as Restylane and Juvéderm, are based on synthesised hyaluronic acid, a naturally occurring compound in the body that breaks down over time, and so are sold as fully reversible, fuelling the idea of dermal filler as fashion accessory. ‘Younger girls wear it like they would a designer bag,’ says Collins.

Unlike Botox, fillers are not classed as prescription medication, and are far less regulated in the UK than in most of Europe, certainly than in America, Australia and even Dubai. Although qualified doctors running aesthetic-medicine clinics are subject to rigorous evaluations by the General Medical Council and the Department of Health and Social Care’s Care Quality Commission, a beautician can go on a day-long course, get a certificate, buy insurance and pick up a needle.

In fact, there is no legislation preventing anybody from buying filler online, ‘taking a syringe and jabbing it into somebody’s face – even complete laypeople who watch a couple of YouTube videos. We found a guy who worked for Ryanair five days a week and did this in his garden shed in evenings and weekends,’ says Collins.

In the wrong hands, unsurprisingly, the consequences can be devastating. When the nurse who usually injected Myott’s lips couldn’t fit her in before she was due to go away for her birthday last December, she did her ‘research’ and ‘found this clinic on Instagram that looked quite good. The lady had a lot of famous people who went to her – reality stars. All the pictures looked amazing.’ She was pleased to find it was cheaper than her usual filler (£130 for 1ml instead of £200), but when she arrived at the clinic in Stockport, she didn’t realise the therapist wasn’t medically qualified.

Within 24 hours, her top lip started to swell with a suspected infection. ‘I messaged the Instagram account and the owner said she couldn’t do anything about it because it was a Sunday and I’d have to go to a walk-in centre,’ says Myott. She was sent home with antibiotics, but two days later her lip burst open in A&E; she had to have surgery under general anaesthetic to remove three abscesses from the right side of her mouth, before spending three nights in a ward on a drip while her infection was monitored. Six months on, she has had to have the stretched skin cut away and the scar tissue that remains is still numb.

In some ways, Myott was lucky. Poorly placed or poor-quality filler can cause a blockage, or occlusion, which can travel between the delicately interconnected arteries in the face, to the eye. ‘There have been a few cases of blindness in the UK,’ says Kambiz Golchin, an ENT consultant and facial plastic surgeon, who practises at the Dr Rita Rakus clinic in Knightsbridge, London, ‘but more commonly what we’re seeing is skin necrosis [where skin dies due to a blocked blood supply]. I’ve had at least four people who have been injected into the blood vessels near their lips present to me as emergencies.’

He has reluctantly become something of a complications expert. ‘I’m seeing more and more, that’s the scary part – a couple of people every week. People think the industry is regulated, like flying, “so it doesn’t matter if I fly on a low-budget airline, they’ll still get me there safely.” That is not the case,’ he spells out. ‘It is not regulated. They will not get you there safely.’

Megan Barton-Hanson before and after: the Love Island contestant in 2012 and last year CREDIT:CAVENDISH PRESS

Golchin charges close to the four-figure mark for 1ml. ‘But this is an important point: a lot of the products we use, we couldn’t buy for £100, and we’re a busy practice with huge buying power. What I charge is a reflection of my 20 years’ experience, not the 30 minutes I spend with you,’ he says.

There’s no such thing as a completely risk-free procedure, even in the safest hands. ‘People who aren’t trained as doctors might well be good injectors,’ says Dr Leonard, who specialises in correcting botched fillers, and recently refilled Myott’s top lip. ‘The problem is, how can you expect them to recognise a complication if they’re not medically trained?’ And while it’s true fillers can be dissolved by an enzyme called hyaluronidase, this can cause allergic reactions in a small number of people, and doesn’t always work, says Leonard.

Problems aren’t confined to the budget end of the market, either. Several months after a micro-needling facial – in which tiny quantities of vitamins are injected under the skin via minute needles – the Telegraph’s Sasha Slater realised a subcutaneous lump was growing between her right brow and the bridge of her nose. ‘It was about the size of a grain of rice,’ she says. ‘When I emailed the facialist to find out what she’d done, she replied saying she might – without asking – have put in some ‘biodegradable threads’. I found it alarming she didn’t even have a record of what she’d done.’

Love Island 2019 CREDIT: ITV PICTURE DESK

The time delay between having the procedure and noticing the problem made it impossible to prove the therapist was at fault, and besides, ‘I wasn’t interested in legal redress, just in making my face look normal again,’ Slater says. She sought out Golchin, who says he had ‘no choice but to do what we call an excision biopsy to remove it’.

This revealed a lump of dermal filler, to which Slater had never consented, and which her body had treated like a foreign object, forming a protective barrier around it. As to why the filler was injected in the first place? ‘The facialist might have just slipped it in to give more of a dramatic effect to the expensive treatment,’ explains Golchin.

The excision itself was swift – a three-minute lunchtime procedure under local anaesthetic, preceded by Botox so that she didn’t frown and rupture the scar – but the cost of remedying the original £265 treatment came closer to £1,850. ‘Often, correcting the damage is a lot more complicated than the procedure that caused it,’ says Golchin. ‘Sometimes we never get back to the starting point, someone’s face is changed for ever.’

Overfilling is also a huge issue, and counselling clients about what is and isn’t achievable is all part of a doctor’s duty of care, says Leonard. ‘If you put too much filler, say, in somebody’s top lip, the lip can’t hold it. It’s essentially a muscle, talking and eating and moving all the time, so the filler will retract and sit past the vermilion border [lip margin]. That’s when you end up looking like a duck.’

Kylie Jenner before and after: She started having fillers aged 15 CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES, WENN

Unscrupulous providers are happy to keep taking the money, no matter how unnatural-looking the results. ‘Because [clients] see themselves in the mirror every day, they get used to it, and then they keep building,’ says Patel. ‘But too much filler really plumps out and stretches the skin. I don’t like that shiny, “done” look at all.’

Some wonder if that look is likely to tail off among celebrities, now it is ubiquitous on the high street. Patel has noticed older clients ‘doing it a lot less’, and mothers of teen daughters rejoiced that large lips might be on the way out this time last year, when Jenner told her 111 million Instagram followers: ‘I got rid of all my filler.’ Three months later, though, her feed showed it was back in place.

Meanwhile, an acquaintance of Myott’s ‘has just done a qualification in fillers and Botox, and she’s very dippy,’ Myott says. ‘I can’t get my head around how someone like that can just go and then be qualified to stick needles in somebody’s face.’