A practitioner offered our reporter Botulax, a product not licensed for use in Britain — and he was far from alone

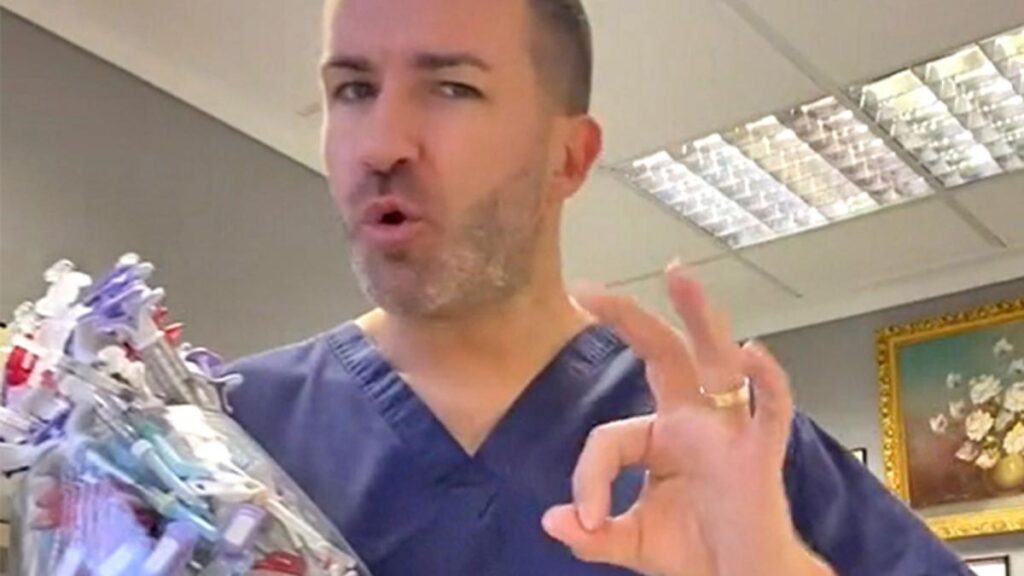

Vilnis Karklins offers treatments at a clinic in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, despite not being registered to practise in Britain

At a beauty clinic above a high street in Wakefield a man in blue scrubs counts 25 points on my face that he plans to inject with an unlicensed anti-wrinkle drug.

The adjoining waiting room features an enormous vase filled with syringes instead of flowers. The walls are decorated with framed pictures of a swimwear model and a former Mrs Universe.

Vilnis Karklins, who says that he trained as a doctor in Latvia but is not registered to practise with the General Medical Council in Britain, warns me that I will need “loads” of jabs for my “very deep” and “long” wrinkles. I am 30 years old, but he suggests that they make me look five years older.

“Maybe stress or something else? Partner? Maybe baby? You have baby?” He asks. “Definitely it will be only in the forehead, 22 [injections]. And some, two or three, around the eyes.”

Karklins works at the Face and Body Aesthetic Clinic in Wakefield, West Yorkshire. Despite his hard-sale tactics, I will not be taking him up on his offer. He is among those using social media to advertise unlicensed versions of Botox to young women on the cheap.

Licensed versions of botulinum toxin, of which the best known is Botox, are prescription-only drugs. They have gone through meticulous safety checks before being deemed safe to use in the UK.

Legally, practitioners in Britain should only be performing injections with licensed products on people who have had this prescribed by a registered prescriber, such as a doctor or a nurse with an additional qualification in this area. The prescriptions should only be made after an in-person consultation.

Karklins has offered to treat me without a prescription. He wishes to use Botulax, a product from South Korea which is licensed there and in other countries but not in Britain.

Under the Human Medicines Regulations 2012, it is unlawful to sell or supply an unlicensed medicine, which includes practitioners selling treatments with these products. As they have not been sourced through an accredited supply chain, there is no guarantee that the vials of Botulax that have found their way to Britain are not counterfeit, with an unknown substance inside branded boxes, or that the product has been stored in a safe way.

Karklins is among many practitioners whom campaigners suspect are using unlicensed products to cut costs or bypass the prescription process. The Times decided to investigate after being warned that “black market” Botox was becoming rife in the beauty industry.

One industry organisation has reported receiving multiple complaints of botched anti-wrinkle treatments every week. Those who have reported problems include women who have been scarred for life, with side effects such as hard and painful lumps across their faces. Many fear they were injected with unlicensed or counterfeit products.

I made an appointment with Karklins because he had referred to Botulax on his personal TikTok profile when showing off boxes of new stock. In one of his posts, he displayed boxes with Botulax branding as decorations on a Christmas tree.

He offered to perform injections across three areas of my face for £145, about half the typical price. The cost of having Botox varies by location and the experience of the practitioner. One reputable high street pharmacy that hires nurses for Botox treatments on over-25s who have prescriptions charges £297 for the same package across the country.

I attended the Face and Body Aesthetic Clinic last month with a male colleague, who posed as my boyfriend. Karklins, who also runs training courses teaching beauticians how to inject, quickly confirmed he used Botulax.

Karklins asked the Times’s undercover reporter to cross the name of one product out and replace it Botulax

At the start of the appointment he presented consent forms for me to fill in. They mentioned treatments with Azzalure, a licensed botulinum toxin product. However, Karklins asked me to cross this name out and replace it with details of a Botulax product. “It’s just form, it doesn’t matter,” he said. “It’s just a brand different.”

When asked why he used Botulax, Karklins said it was “better” and “cheaper”. With Botox, he said, appearing to refer to the licensed brand name, “I can never do discounts”. Clients did not want to pay the same prices in Wakefield as they did in cities such as London, he claimed. When I asked if I needed a prescription, he said: “No, nobody”.

I asked if anything could go wrong. Even treatments using licensed products and under the watch of registered medical professionals carry some risks. “Nothing can go [...] wrong”, Karklins replied. “If you know where you need to put it, nothing goes wrong.”

He also described a lip filler treatment that he offered, suggesting he performed this on clients as young as 16 or 17 when they came in with their family members. Last year it became illegal to give fillers to under-18s, whether or not they have parental permission.

We also had an appointment with Samantha Bennett, an aesthetic practitioner from Manchester who visits people at home to do anti-wrinkle injections. She suggested I should have 11 injections in my face and offered to use Innotox or ReNTox, also botulinum toxin products from South Korea that are not licensed in Britain.

She showed us the products and said “nothing can go wrong” and that “it never has in the years that I’ve been doing it”.

Previously, during a phone call to arrange the appointment, she said that Innotox was “like gold dust at the minute”, adding: “Basically it’s a premixed product so it’s really strong. Everyone has gone mad for it.”

In total, a colleague and I attended three in-person appointments with practitioners across the north of England and confirmed they were using an unlicensed product. In each case, we made excuses to leave before having any treatments.

The third practitioner, Janine Walker, who runs a business called Envy Esthetics, in Preston, Lancashire, advertised Botulax injections in a Facebook post.

The appointment took place in a treatment room at Walker’s house on a quiet residential street. She had previously worked as an accountant but “started doing nails and things like that” during the pandemic. She said that Botulax had not been used in her training but that she found the product after reading reviews online. She appeared to believe it was a licensed product.

Walker did not use hard-selling tactics. She said the lines on my face were “very fine” and also warned about possible side effects such as headaches.

There is no suggestion that any of the practitioners botched treatments or that any specific product is linked to poor results or side effects. Problems can be caused by other issues such as bad hygiene or poor injecting technique.

Save Face, a register of practitioners that also raises awareness of safety issues and standards, said that it was increasingly receiving reports of problems caused by anti-wrinkle treatments. Its latest published figures from 2020 show it received 270 of these complaints that year, up from 210 in 2019. Of the 270 complaints, 206 of those were regarding possible unlicensed or illegitimate products.

Ashton Collins, director of Save Face, said: “Either someone is knowingly using an unlicensed product to cut corners and put profit before your safety, which is outrageous, or they are so ignorant and unaware of what the legislation and regulations are around medicines in this country.”

Black market Botox was readily available on the internet for non-medics to purchase from multiple sources. I contacted two companies posing as a beautician and wanted to buy the product to use on my clients. The companies, both based in Britain, offered to sell it to me with no questions asked.

They included Shafaa Pharmacy Limited, which stated on its website that “people over profit” was the “core principle” of its business. The company sold a variety of botulinum toxin products, including ones with and without licences. Other items for sale included hand cream, hazmat suits and thermometers.

A listing for Bocouture, a product that can legally be sold in the UK, carried a disclaimer stating that it could be only sold to licensed practitioners. However, there was no similar warning on listings for Botulax.

I inquired about Botulax and asked a call handler if I would need to show any identification in order to buy it. He said: “We are going to send you a description on how you are going to use it [...] you don’t need a prescription as well.” He said I would be able to order it and receive it the next day.

Dr Tijion Esho, a leading cosmetic doctor specialising in non-surgical procedures, also treats clients who have undergone botched treatments. He recently saw a woman who had lumps in her forehead after being injected with an unknown botulinum toxin product. She showed him pictures on her phone of others who had suffered similar reactions.

Esho concluded that it was “definitely a black market Botox” that was causing the problems. “It wasn’t something I have ever seen before,” he said.

Esho has seen increasing numbers of cases like this over the last five years. In order to treat the problems he needs to know which drug was used. “Without that history I don’t go forward”, he said. “Then I am putting the patient at risk as well as myself.”

Esho’s clinics try to help clients discover what has happened if contact with the practitioner has broken down. This has even involved members of staff phoning and pretending to be a patient. But not every corrective practitioner will go to these lengths, and some victims of botched work may struggle to find someone who will treat them.

Nora Nugent, a cosmetic surgeon and council member of the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons, said that not knowing the product complicated cases where a patient had experienced an allergic reaction, as they were left unaware of what product they were allergic to.

Nugent said reputable clinics and hospitals would either buy products from a wholesale pharmacy or have an arrangement with the manufacturer. “The problem when you’re circumventing all this is that you’re also circumventing any regulations and standards. You just don’t know what you are getting. You don’t know that it meets the same standards,” she added.

The medicines regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, has begun an investigation into our findings and said it would “take appropriate regulatory action where any non-compliance is identified”.

A spokeswoman added: “If a medicine is not authorised, there is no guarantee that it meets quality, safety and effectiveness standards required in the UK. This can endanger the health and welfare of people who take them.”

Karklins and Walker did not respond to requests for comment. Bennett said that she was not aware she had been using unlicensed products and that she bought them from a company that trained practitioners.

“I’ve done nothing wrong,” she said. “Botulax, I’ve used that for years. ReNTox and Innotox is a new product that I’m using. It is getting good results. But I wasn’t aware that you’re not supposed to use this.”

Shafaa Pharmacy Limited said that it was a licensed pharmacy, overseen by a doctor, and that it had “the right to sell Botulax”.

Hugel, which manufactures Botulax, said that the product had undergone rigorous clinical trials, was high-quality, safe, and licensed for use in 28 countries. However, it said it should not be ordered or used by practitioners in Britain.

A spokeswoman said: “We cannot guarantee the Botulax product used in UK is a real Botulax product or counterfeit one. Even if it is an actual Botulax product leaked from Korean market, no one can guarantee if the product was stored and distributed appropriately. We strongly recommend consumers and practitioners to use products with official marketing approval.”

Hugel said it was inaccurate to describe Botulax as a black market product and that problems such as facial lumps could not be related to legitimate Botulax. It said it closely monitored the supply of products claiming to be Botulax and took legal action against unauthorised distributors. It said it was preparing for a version of Botulax with a different brand name to be licensed in Britain in the near future after it recently completed a European approval process

Pharma Research Bio, which manufactures ReNTox, did not respond to requests for comment. Medytox, which manufactures Innotox, said it did not sell Innotox in countries where it was not licensed, including in the UK. A spokesman said: “Medytox will take necessary measures if any illegal activities related to Innotox’s sales are found.”

Almost a decade ago a review commissioned by the government into the beauty industry warned that non-surgical cosmetic treatments, such as lip fillers and Botox injections, were “almost entirely unregulated” in Britain (Paul Morgan-Bentley and Charlotte Wace write).

Sir Bruce Keogh, then NHS medical director, led the work in 2013 and wrote of his surprise to discover the lack of legal protections given the “major and irreversible adverse impacts on health and wellbeing”.

“In fact,” he wrote, “a person having a non-surgical cosmetic intervention has no more protection and redress than someone buying a ballpoint pen or a toothbrush.”

Nine years on, experts warn that there is still a “complete absence of regulation”, which puts vulnerable people tempted by unnecessary cosmetic procedures at serious risk of harm.

There have been some changes, most notably a new law making it illegal to perform these injections on under 18s, which came into force last year. However, as the Times investigation reveals today, practitioners with no formal medical qualifications are still able to administer the injections, with many openly advertising to young women on social media and some using unlicensed drugs that have not been checked for safety in Britain. Campaigners warned of increasing reports of botched treatments, with some women left scarred for life.

This “black market Botox” is booming because unlicensed products can easily be ordered to Britain online. This allows practitioners to offer treatments on the cheap and for them to bypass the legal prescribing process.

Licensed brands of botulinum toxin, of which the best known is Botox, are only meant to be administered after a prescription is given by someone licensed to do so — such as a doctor or a nurse with additional training — after a face-to-face appointment. However, reporters found this was not enforced and none of the practitioners they approached undercover said this was needed.

This matters because the consequences can be life-changing. Manufacturers of products that are not licensed in the UK said if these appear to be on sale here the product inside the vials may well be counterfeit. It is impossible to know what is being injected into unsuspecting young people’s faces.

Victims of botched treatment may struggle to receive any compensation. Doctors are nervous about performing corrective treatments if they cannot be sure what product was used initially. Some beauticians who have found themselves as the focus of complaints have gone to ground before re-establishing themselves under a different name, once again openly advertising their services, apparently without any fear of repercussions.

Another report published last year after a year-long inquiry into non-surgical cosmetic treatments identified many of the same issues found by Keogh. The all-party parliamentary group on beauty, aesthetics and wellbeing announced its findings in July with a press release, titled: “MPs call on government to address complete absence of regulation over Botox and fillers and say maintaining the status quo is not an option”.

The report found that there was an expanding array of new treatments and a “rapid growth” in their popularity, but that “the UK’s licensing and regulatory landscape has not kept pace with these changes”.

The cross-party group of MPs wrote that despite Keogh’s review, “little action has been taken and the government has largely left the industry to self-regulate”. Their recommendations included: psychological pre-screening for people who wanted to have these treatments; national minimum standards and regulations for practitioner training and qualifications; improved licensing of drugs; further legal changes to protect teenagers from more treatments and a requirement for social media firms to do more to curb misleading posts promoting these treatments.

In light of this newspaper’s findings, Sajid Javid, the health secretary, said that officials were investigating what changes were needed “to ensure no one is harmed”.